In Defence of American Empire

You’ll miss the Yanks when they’re gone

Part 1: America’s departure from the British Empire

There was a time when many people, at least in Europe, thought that empire was a good thing, bringing the benefits of humanitarian emancipation, the ending of endemic inter-tribal warfare, modern science and technology, and moral and religious enlightenment to the benighted places and peoples of the earth. Those (like me) whose parents were born before 1914 are separated from that era by a single generation. By the end of the First World War, however, several mighty stars in the imperial firmament had fallen and the future of those that remained looked insecure. Moreover, the sheer fact of imperial dissolution—whether Ottoman or Austro-Hungarian or German or Russian—was given moral impetus, when, at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, Woodrow Wilson lent American weight to the notion that nations possess a natural right to self-determination. Since then, empires have commonly been identified with ‘imperialism’, and ‘imperialism’ with oppression and exploitation.

It requires little reflection to grasp why Americans instinctively identify themselves as anti-imperialist. After all, the United States was born out of a struggle to throw off the constraints of the British Empire. According to the conventional patriotic story, the war of 1775-83 was one of national ‘freedom’ against imperial ‘tyranny’. Yet the whole truth is not quite so straightforward.

What was the tyranny supposedly at issue? Answer: monarchy with absolutist, unconstitutional tendencies, manifested in the arbitrary imposition of intolerable taxes, and enforced by brutal military coercion. Here we have the imperialist archetype of empire. But is this an accurate description of the actual behaviour of George III and the British government? Or is this archetype in fact a stereotype? It is true that Whig politicians in Britain believed that the king was subverting the Constitution by using royal patronage to control (buy) Parliament, and that this reading of events influenced their confrères in colonial America. It is true that in 1765 the Grenville ministry unilaterally imposed direct taxation upon the colonies, which was unprecedented, by way of the Stamp Act.[1] It is true that the American colonists did not have direct representation in Westminster. And it is true that the behaviour of British troops in and around Boston on the eve of war was sometimes provocative and sometimes brutal.

Americans came from a society composed of a much higher proportion of self-made people, especially independent farmers, to whom social deference did not come naturally.

All that is true; but the following is also true. First, contemporary historians judge that Whig anxiety about another resurgence of absolute monarchy in England was altogether overwrought: the buying of political influence by the Crown was a serious problem, but it fell a long way short of what the word ‘tyranny’ connotes.[2] (And, one might mischievously point out, the buying of political influence—by private individuals and commercial corporations—is something that many Americans today seem largely untroubled by.)

Second, the Townsend taxes had been levied to help defray the costs of the French and Indian War of 1754-63, which had secured the English colonies in America, but had resulted in a doubling of the British national debt and a quintupling of the expense of colonial defence and administration.[3] Nevertheless, thanks to a combination of American resistance (including mob violence), British mercantile lobbying, and a change of ministry, the Stamp Act was repealed the following year. Besides, that issue rose and fell nine years before the outbreak of war in 1775. The infamous customs duty on tea that did precipitate war was quite different: it was an ‘external’ tax, the likes of which had long been used by the imperial government to raise revenue. Third, while it is true that the colonies did not elect Members of Parliament to Westminster, they did have agents in London, who recruited British M.P.s to their cause. American views were not unrepresented; and even if they had been represented directly, they would not necessarily have prevailed. And fourth, eighteenth century soldiery was generally unruly and brutal: come the war, even American patriots did atrocious things. Yet the most famous instance of British military brutality is surely the ‘Boston Massacre’, when bloodthirsty redcoats gunned down innocent civilians—except that, as historians now acknowledge, the redcoats weren’t so bloodthirsty, nor the civilians so innocent.

To this picture, three further factors need to be added. First, as became clear during the French and Indian War, there was a significant cultural gap between the American colonists and their British cousins. The latter came from a society in which aristocrats expected and received a measure of deference from their social inferiors. Americans came from a society composed of a much higher proportion of self-made people, especially independent farmers, to whom social deference did not come naturally.[4]

Second, one of the manifestations of ‘tyranny’ against which the colonists reacted was the British granting of religious tolerance to Roman Catholics in Quebec in the Quebec Act of 1774. Roman Catholicism being equated with political tyranny, this was taken as a further sign of the absolutist tendencies of British government. In fact, it was nothing of the sort. The granting of tolerance was merely an act of political prudence (and none the worse for that), aimed at encouraging the Catholic French to live peaceably under British rule.

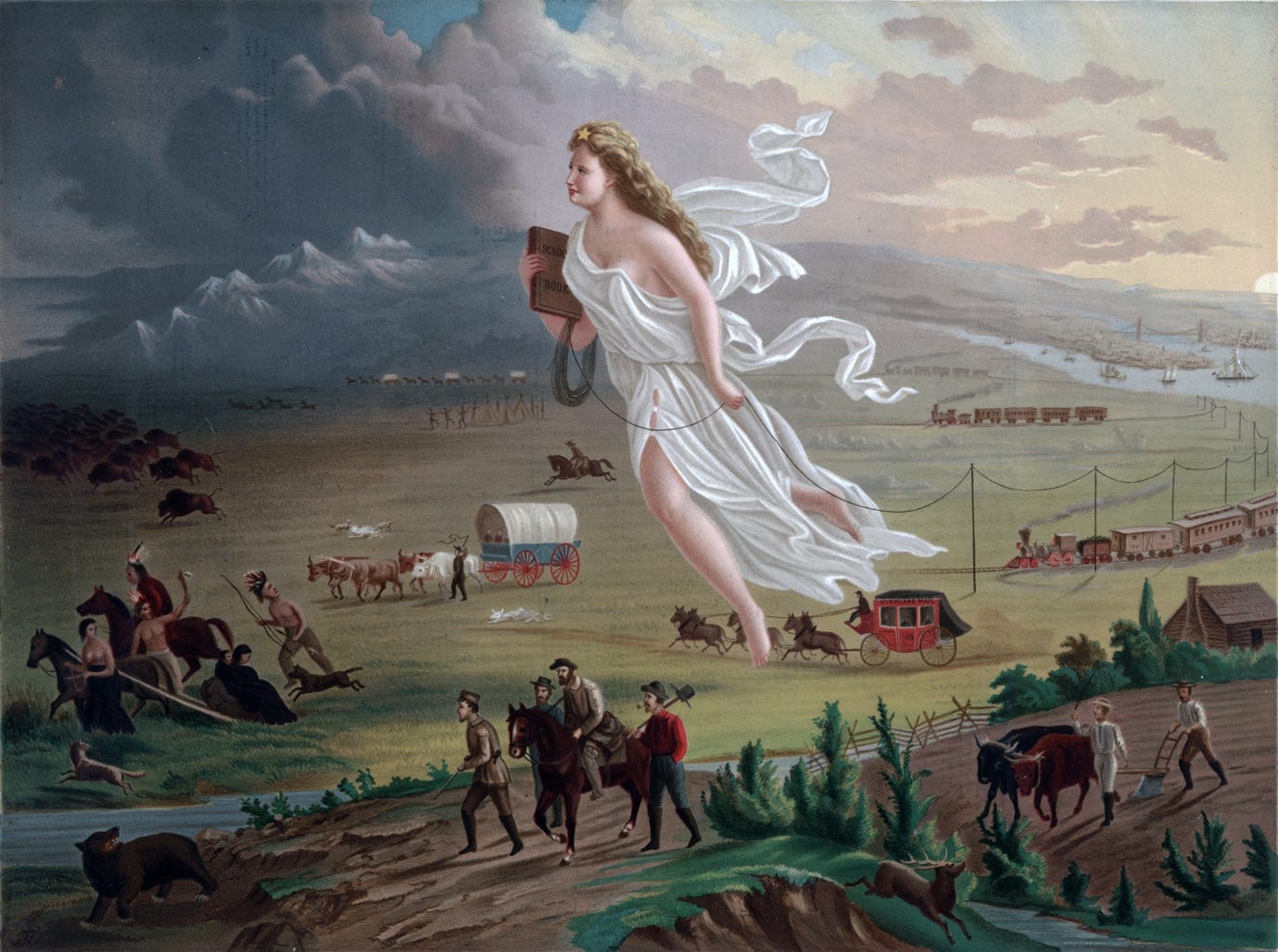

Third and finally, in the aftermath of the French and Indian War, the British had promised native Americans that colonists would not invade and settle the lands west of the Appalachians. To the colonists, of course, this was another manifestation of ‘tyranny’—a deeply unwelcome constraint upon what they saw as their natural right to expand.[5] Urging the claims of the United States upon the Mississippi valley against Spain, James Madison, the chief architect of the U.S. Constitution, wrote to Lafayette in 1785: “Nature has given the use of the Mississippi to those who may settle on its waters, as she gave the United States their independence…. Nature seems on all sides to be reasserting those rights which have so long been trampled on by tyranny and bigotry… If the United States were to become parties to the occlusion of the Mississippi they would be guilty of treason against the very laws under which they obtained and hold their national existence.”[6] On the natural moral claims of the native Americans, of course, Madison was silent.

That, then, is the more morally complicated history of the war by which the American colonies seceded from the British empire. To summarise that conflict as a battle between colonial ‘liberty’ and imperial ‘tyranny’ does not begin to do the details justice, and it misleads far more than it informs. Yes, the imperial centre was remote, both in miles and increasingly in culture. Yes, the representation of the colonists and their interests in the imperial law-making and tax-imposing parliament was only indirect, and so weaker than it could (and arguably should) have been. But the principle that the primary beneficiaries of the French and Indian War should bear a fair share of its costs is incontrovertible; and the practice of ‘external’ taxation by which the Government sought to realise that principle had long been established. What is more, in this case it was the empire that upheld the liberty of Roman Catholics to practice their religion in Quebec, and the liberty of native Americans not to be invaded—and the empire upheld these liberties against the colonial anti-imperialists. Empires do not always live down to their stereotype, any more than patriotic ‘freedom-fighters’ always live up to theirs.

Part 2: The American Empire

[T]here is no reason at all to suppose that Beijing would be a better steward of dominant imperial power than Washington.

Judging by the past, an empire need not live down to its ‘imperialist’ stereotype as an oppressive, exploitative, tyrannical power. Indeed, sometimes its power has been positively emancipatory. Americans, therefore, ought to become more reconciled to the idea that the United States in fact possesses imperial power, should retain it, and has a duty to wield it well rather than badly.

The truth is that international affairs has always been characterised by the dominance of some states over others. Asymmetry of power is a fact of international life, which the post-1945 presence of international institutions does not remove and is never likely to. While the United Nations provides important means of international communication, negotiation, co-ordination, and restraint, it is no substitute for nation-states, upon which it depends entirely for its resources. And some nation-states are more powerful than others, dominating either formally through direct territorial control or treaty of alliance, or informally through economic clout or soft cultural power. Whether formal or informal, this international dominance is imperial. From 1815 to 1914 the dominant global power was Britain and its empire. Arguably from 1919, more so from 1945, and most clearly so from 1989, that power has been the United States.

To many people of liberal conviction, ‘domination’ and ‘dominance’ connote oppression and tyranny. But they need not. Surely, we want the police to dominate the mafia, liberal democracy to dominate autocratic tyranny, self-defensive Ukrainians to dominate unjustly invading Russians. To dominate need to be to domineer, and in a world of inevitably unequal power, it is better that the just (all-things-considered) are more powerful than the unjust.

It is true, of course, that empires, like nation-states and municipalities and churches, are run by sinners. Consequently, they sometimes do bad things, sometimes very bad indeed. Thus, for example, the British Empire presided over one hundred and fifty years of slave-trading and slavery from approximately 1650. And yet in 1807 the British Empire renounced the trade and in 1833 it abolished the institution, and then spent the remaining century and a half of its existence suppressing both of them all over the world. Indeed, the American political scientists Chaim Kaufmann and Robert Pape have written that Britain’s effort to suppress the Atlantic slave trade (alone) in 1807-67 was “the most expensive example [of costly international moral action] recorded in modern history”.[7]

In the US case, the colonisation of the American West in the late 18th and early 19th centuries involved broken treaties and incidents of unjustifiable bloodshed. Nonetheless, native Americans now enjoy the privilege of equal citizenship in one of the most prosperous and liberal countries on earth. And in the 20thcentury American industry and arms played a vital role in overcoming the genocidally murderous Nazi subjugation of Europe and the brutal Japanese oppression of Asia. And, notwithstanding the moral ambiguities of the dropping of atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, American imperial dominance from 1945 established liberal democracy in Germany and Japan, and secured it worldwide against the imperial expansion of Soviet Russia and Communist China.

Of course, those who possess dominant power are always tempted by hubris. Some would argue that the US succumbed to that temptation in the years following the disintegration of the Soviet Union, leading to overambitious plans to transform Afghanistan after 2001 and the overoptimistic invasion of Iraq in 2003. Certainly, America’s staunchest allies felt badly slighted when she started to withdraw from Afghanistan in 2021 without bothering to inform them of her plans.

Nevertheless, the fact that imperial power can be ill-used does not mean that it should simply be abandoned. Rather, it should be used better. So, even if the United States should do penance for broken treaties with native Americans during its original imperial expansion westward, that does not mean that it should eschew all imperial power and simply retreat from the world today. For what the US jettisons, its rival—China—will pick up. International politics abhors a vacuum. And there is no reason at all to suppose that Beijing would be a better steward of dominant imperial power than Washington. Indeed, if the plight of Hong Kong and the Uighurs is anything to go by, there is good reason to suppose that it would be a lot worse.

For sure, being an imperial power is burdensome. But the burden is borne in part to ensure that one’s own national people and their way of life are kept secure. For those who do not dominate will themselves be dominated.

And, yes, subordinate allies can be testy and ungrateful. While taking for granted the fruits of the post-1945 pax Americana, European peoples have often been reluctant to contribute a fair share of the cost of their own defence against Soviet, and now nationalist, Russia. But, if that (rightly) irks Americans, they might allow their irritation to be reined in a little by the thought that, once upon a time, their colonial forebears irked the imperial British a lot by their reluctance to pay a fair share of their own defence costs.

At bottom, however, the justification for wielding dominant, imperial power lies in the value of the goals it is made to serve. Of course, the first duty of a national government is to defend and promote the security and prosperity of its own people—and to do that for 332 million American human-beings is hardly a selfish act. But the defence and promotion of the domestic security and well-being of one people depends upon making and keeping the international environment friendly rather than hostile. So, what is defended and promoted at home must also be defended and promoted abroad. And if what is defended and promoted includes values and institutions generally important for human welfare—such as the rule of law, an incorrupt civil service, and legal rights—then foreign peoples will benefit, too.

The United States is not the only trustee of such values and institutions, but, thanks to the gifts of Providence and its own achievements, it happens to be the most powerful one at this time. Its primary duty to its own people obliges it to use its dominant power to serve others secondarily. For if it should surrender its dominant international power, other states, less humane and liberal, will pick it up. The US has a vocation to shoulder the imperial burden, certainly for the sake of Americans, but also for the sake of the rest of us.

NOTES

[1] David Reynolds, America, Empire of Liberty: A New History (London: Penguin, 2010), p. 58.

[2] For a new, sympathetic account of King George III, see Andrew Roberts, George III: The Life and Reign of Britain’s Most Misunderstood Monarch (London: Allen Lane, 2021).

[3] Reynolds, America, p. 56.

[4] This is Fred Anderson’s thesis in Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the fate of the empire in British North America, 1754-1766 (London: Faber, 2001).

[5] Alan Taylor regards the British prohibition of American settlers from the trans-Appalachian West as a cause of the subsequent revolutionary conflict equal to that of the imposition of taxes (American Revolutions: A Continental History, 1750-1804 [New York: W. W. Norton, 2016], pp. 6, 77).

[6] Ralph Ketcham, James Madison: A Biography (Charlottesville: University of Virginia, 1990), p. 177. See also pp. 96-7.

[7] Chaim D. Kaufmann and Robert A. Pape, “Explaining Costly International Moral Action: Britain’s Sixty-Year Campaign against the Atlantic Slave-Trade”, International Organization, 53/4 (Autumn 1999), pp. 634-637, esp. p. 631.

Anti-imperialism allowed me to feel sympathy for the Native Americans, and therefore allowed me to feel pride in Britain's struggle against the American colonists, wiping away years of liberal shame at the hands of Mel Gibson's "The Patriot", and other such pro-American works.

Professor Biggar sees this as imperialism, but I cannot deny a certain anti-imperial tinge to what he writes here.

If I am proud of Salisbury and Metcalfe standing up for the better Indian Princely states, am I an out and out imperialist, or a hybrid imperialist/imperial skeptic?

It seems to me that not all anti-imperialism is bad, especially when viewed with a conservative attitude.