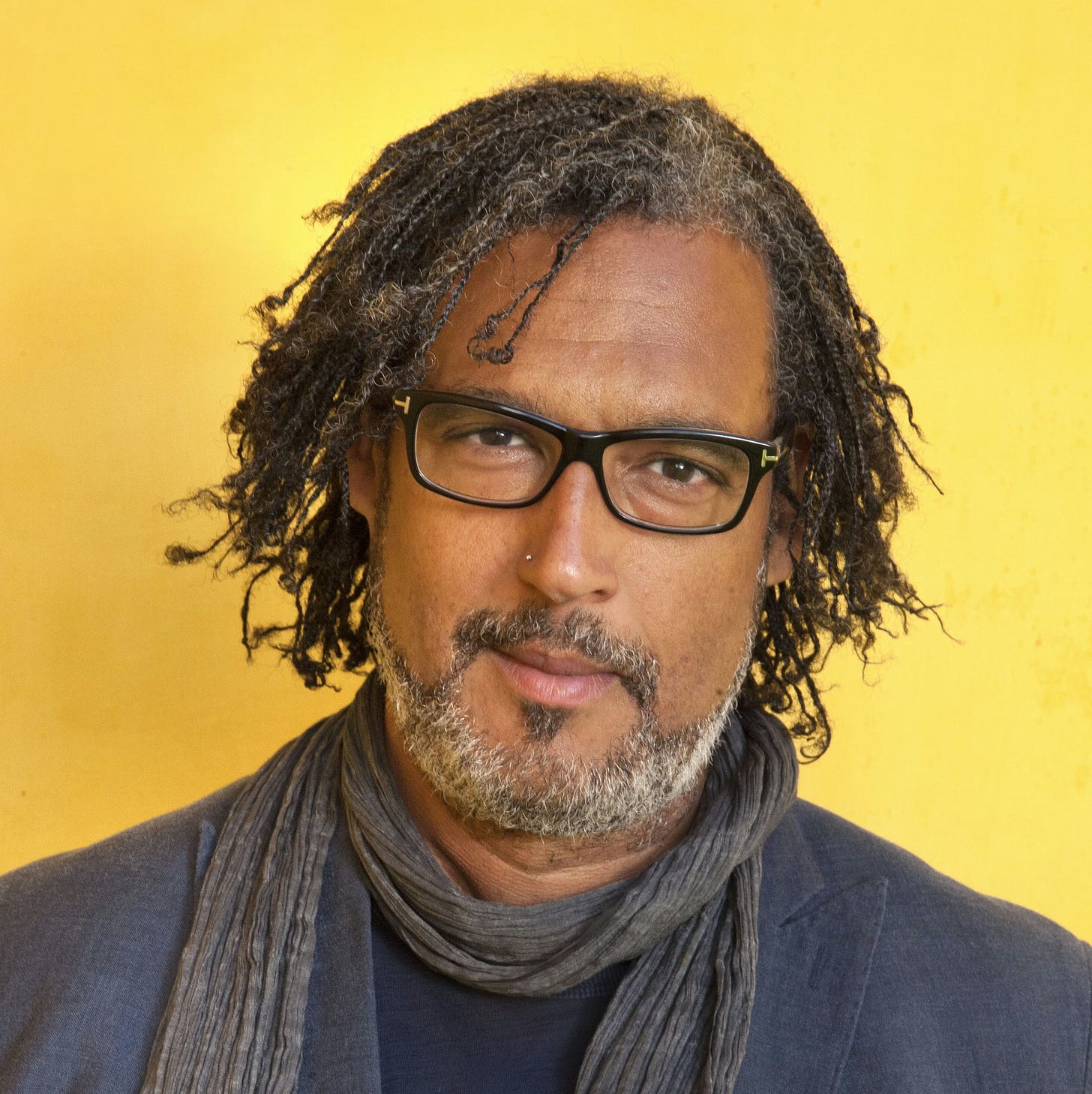

Olusoga's 'Empire'

No room for nuance at the BBC

Let us do what David Olusoga doesn’t do. Let’s be fair. Viewers of his three-part BBC 2 series, ‘Empire’, do learn many things that are true about the British Empire. They learn that, as empire-builders, the European British weren’t the only or the first, coming after the North American Powhatan and the Indian Mughals. They discover how Britain’s imperial expansion began with adventurers heading west across the Atlantic to North America and merchants sailing east to India in the 16th and 17th centuries. They find out how at the end of the 18th century the American Revolution robbed the British government of a destination for convicts and inspired the settlement of Australia. They’re told of the migration of up to two million Indians as indentured labourers around the Indian Ocean and as far as the Caribbean in the 19th and early 20th centuries. And they hear how the Empire reached its height in the early 1920s, only to have vanished less than fifty years later.

Moreover, not everything viewers are told is bad. They’re told that native Americans sometimes welcomed English colonists because they wanted the things they traded and coveted their alliance against native enemies. They learn of “the British commander” in New York City who, in 1783, defying the terms of the Treaty of Paris ending the American War of Independence, evacuated African American loyalists rather than return them to their ‘patriot’ slaveowners. And they hear the story of an Indian migrant whose indentured servitude enabled him to buy land in what is now Guyana and make a better life for himself.

So, positive truths are voiced. But they’re all incidental to the central story, which is overwhelmingly negative, as the sinister music growling in the background signals. Each episode opens with the same voiceover by Olusoga, which includes the observation that “scattered across the world are the ruins of the British Empire- … slave fortresses, schools, railways, and prisons”. Observe: yes, schools and railways, but bracketed by—contained within—slavery and repression. During the series, the only imperial Britons graced with names and faces are villains such as Robert Clive, John Batman, and John Gladstone. William Wilberforce’s surname appears only momentarily on a street sign with no explanation given. And whereas the evils of slavery take up a large part of the first episode and some of the second, Britain’s unprecedented abolition of the slave trade and slavery, and its century-and-a-half’s worth of worldwide suppression of them, are allotted an offhand twenty-five seconds.

Viewers who know nothing about the history of slavery learn that the British practiced it, but not that the practice was universal, conducted by people of every skin colour on every continent. They are given the impression that enslavement was something imposed by whites on blacks, not being told that black Africans had been enslaving other Africans for centuries before the Europeans arrived, and that, twenty years after British abolition, the Fulani people of what is now northern Nigeria were running vast plantations, where they exploited as many slaves (four million) as in the whole of the then United States. Viewers are also told, several times over, that Britain’s wealth today derives from historic British slavery, but not that this is a highly controversial thesis rejected by the most eminent living historian of transatlantic slavery, David Eltis, and by the 2025 Nobel Prize winner for economics, Joel Mokyr. And they hear it asserted that the legacy of slavery continues to misshape the lives of the descendants of slaves, without being given any explanation of why those descendants in Barbados are significantly better off than their peers in Jamaica and far better off than those in Nigeria, some of whom are the descendants of slave-raiders, traders, and owners.

About the settlement of Australia we learn that some convicts (somehow) managed to better themselves, but not that this was the fruit of the deliberate policy of rehabilitation promoted by the remarkably humane colonial Governor of New South Wales, Lachlan Macquarie. Thereafter the story of Australia is made to focus on Tasmania, where settlers displaced aboriginal peoples, using violence against them “from the beginning” and intent upon extermination, and culminating in their forced removal to Flinders Island. There, “an ancient people, hunter gatherers, with their own complicated culture and spirituality, [were transformed] into sedentary, Christianised, obedient peasants…. people promised sanctuary were instead subjected to the systematic destruction of their culture”.

Among many things, what’s missing from this sorry tale is context. The truth is that modernity was coming to aboriginal Australia sooner or later, one way or another, and that the impact on stone-age peoples was bound to be shocking. If it hadn’t been the British, it would have been the French or the Americans. It could even have been the Māori, who, if not exactly modern, were far more technologically, politically, and militarily advanced than native Australians or Tasmanians. They were also more warlike: when they invaded Chatham Island in 1835, they slaughtered ten per cent of the Moriori people and enslaved the rest. In contrast, when the enlightened British admiral, Arthur Phillip, landed the First Fleet at Sydney Cove in 1788, he ordered his men to share their catches of fish with the aboriginals, allowed them to wander into his house and sit down and eat with him, provided medical aid when they were struck down by smallpox, and refused to retaliate when speared in the thigh. So, no, the original encounters between the British and aboriginals in Australia were actually not violent.

And when, in 1830, it seemed to Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur that the only way to save Tasmanian aboriginals from settler violence was to separate them onto a ‘reserve’ where they would have time to adapt to the new world that had suddenly come upon them, he set about the Flinders Island scheme. Even the left-of-centre historian, Henry Reynolds, acknowledges that Arthur had no wish “more sincerely at heart than that every care should be afforded these unfortunate people” and that he “begged and entreated” George Augustus Robinson, the commandant of the aboriginal settlement on Flinders Island, to “use every endeavour to prevent the race from becoming extinct”. Reynolds also argues that Arthur matched his words with deeds, ensuring that the aboriginals were better provided for–not least in medical care–than other welfare recipients in Tasmania such as orphans, paupers and convicts. This well-intentioned endeavour was not sufficient, however, to prevent most of the aboriginal people on Flinders Island from dying, mainly from respiratory diseases inadvertently imported from Europe. None of this complicating detail, however, is allowed to muddy the stark, simple colours of Olusoga’s story of wanton white oppression of black victims.

He applies the same white-versus-black straitjacket to the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya from 1952-60. The cause, we’re told, was the theft of land by white settlers from the Kikuyu. Although the vast majority of those killed were African, it was only the killing of white settlers that shocked the colonial authorities into action. This action consisted of hanging 1,090 convicted rebels, presiding over the castration with pliers of some detainees, and permitting the beating to death of eleven of them at the Hola detention camp.

What we’re not told is this: