On Shame and Guilt

Yasukuni Reflections

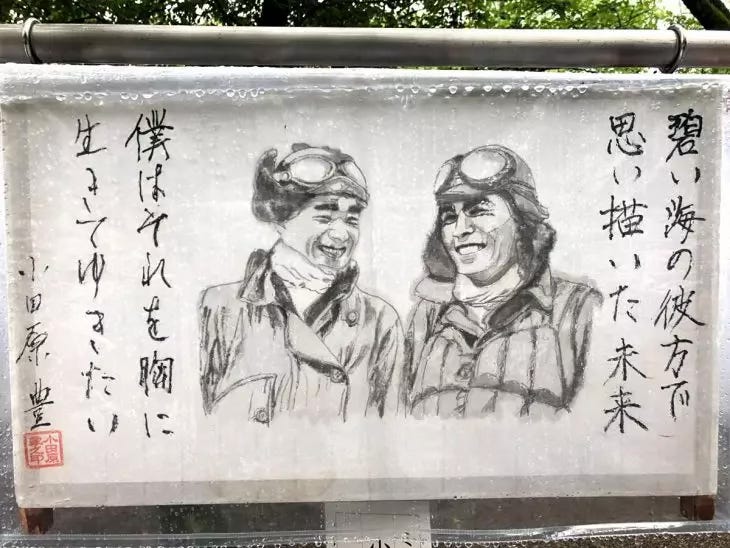

If ever you find yourself in the centre of Tokyo, make your way to the north-west corner of the Imperial Gardens, and turn left. A few minutes will bring you to the Yasukuni-jinja, Japan’s most controversial site. This is the national shrine to the war-dead, whose two and half million resident “glorious souls” include fourteen Class A war criminals.

A hundred yards to the right of the main shrine stands a museum, the Yushukan. Upon entering it, a visitor finds himself immediately face to face with a locomotive.

Now, when an Anglo-Saxon puts together Japan, Second World War, and locomotive, he arrives at one thing only: the ‘Burma Railway’. This is the railway that was hacked through the Burmese jungle partly by Allied prisoners-of-war, who were treated as slave labour and perished in their thousands. Over 12,000 Westerners died—about one in five—alongside perhaps 90,000 Asians.

So our Anglo-Saxon visitor beholds the locomotive with a mixture of disbelief, rising horror, and curiosity. He approaches the machine, looking for an explanatory text. Finding it, he learns that this locomotive is one of ninety that ran along the Burma Railway. He also learns the name of the military unit responsible for the railway’s construction. But of the Allied prisoners, the slave-labour, and the number of their deaths he learns nothing at all.

The Burma Railway wasn’t Auschwitz, either in genocidal intent or in murderous scale. But it was similar in its cruel contempt for human life. So the experience of confronting this Tokyo locomotive is analogous to stepping into a museum in Berlin and being confronted by one of the trains that shipped Jews to Auschwitz, and then reading an explanation that omits any mention of its cargo or the nature of its destination. If there were such a museum in Berlin, I’d have found it.

When our Anglo-Saxon ventures deeper into the Yushukan, he eventually discovers the exhibition on the 1930s and World War Two in the Far East. And here he learns that Japan’s imperial expansion was in fact a war of liberation, waged on behalf of subjugated Asian peoples, against Western colonial domination. And he learns that, even though Japan lost the war militarily, she won it politically, since the example of her early victories over the French in Vietnam, the Americans at Pearl Harbor, and the British at Singapore helped to inspire anti-colonial movements worldwide and so succeeded in ridding the world of European empires.

He also learns that what is known outside Japan as ‘the Rape of Nanking’ (1937-8) is referred to demurely in the museum as ‘the Chinese incident’. And that whereas the ‘Rape of Nanking’ is reckoned to have involved the indiscriminate massacre by Japanese troops of about 300,000 Chinese civilians, ‘the Chinese incident’ only involved the severe treatment of Chinese troops who had violated the laws of war by disguising themselves in civilian clothes.

So: no repentance and no apology. No repentance and no apology for anything at all done by Japan in the 1930s and 1940s.

The text-book explanation for this lies in the distinction first made by the American anthropologist Ruth Benedict in her 1946 book, The Chrysanthemum and the Sword: Patterns of Japanese Culture, between ‘shame’ cultures and ‘guilt’ ones. In a ‘guilt’ culture such as our own, attention is turned primarily inward. It heeds the inner voice of conscience, the still small voice that can be heard by no one else in the world. It beholds the eye of God, which reaches even into the private depths of the heart.

By contrast, in a ‘shame’ culture attention is fixated on how other members of society view you. And the urgent priority is to maintain face, not to admit fault, not to expose oneself to social condemnation. According to Benedict, Japan is the paradigm of a ‘shame’ culture.

Benedict’s work has provoked controversy in Japan and attracted criticism for mistaking the posture of a specific class for that of a whole people. What’s more, since the 1950s Japanese leaders have indeed made public apologies and expressions of remorse. Nonetheless, the Yushukan’s brazenly impenitent narrative suggests that The Chrysanthemum and the Sword does identify an influential cultural disposition that remains alive and well in Japan today.

That said, the distinction between shame and guilt doesn’t really explain the resistance to repentance and apology. For we can feel inwardly guilty and still refuse to admit and confess it out of terror at social shame. The crucial question is why some cultures consider shame unbearable. And the answer is that the individual’s sense of self-worth can’t survive it, since forgiveness is nowhere on the horizon. Personal failure is absolute; there’s no way back from public humiliation.

In cultures such as our own, however, centuries of Christianisation have disposed us to assume that forgiveness is readily available, everywhere standing at the door, eager to run and embrace the returning Prodigal. Forgiveness even for wrongdoing that is hidden from human view or beyond human repair. Because if there is a God, and if he wears the face of Jesus, then his eye beholds us, even as it judges, with compassion. And this eye, being God’s, is omnipresent.

Where forgiveness is thought to be always at hand, the admission and confession of guilt become moves that are ultimately constructive, not destructive. They become worth the costs of social shame.

This Christian understanding of the confession of guilt—of public repentance—is vital for human well-being. It’s vital, because, if repentance and apology are thought insufferable, then face may be saved, but only by making it rigid with impenitent self-justification. Such a hard and unyielding face injured victims simply cannot trust—since an unchanged oppressor is likely to repeat his oppression. And without trust, there can be no reconciliation. And without reconciliation, no peace.

Excellent Nigel. When I was a soldier I was not allowed to visit the shrine; I now do so to see how history is deliberately distorted in the way you have described here. Thank you.

Repentance, forgiveness, resurrection. I don't think we can survive as individuals or societies or a species without these attributes. And sadly missing in some cultures so that grievances are nurtured and perpetuated for centuries...and misery for everyone concerned.