Project Spire

The Church of England is emptying its pockets to appease woke ideologues. It should stop.

In November 2023 the Church Commissioners of England committed the Church of England to begin making reparations for its involvement in transatlantic slavery, via Project Spire, to the tune of £100 million. Yet, as a rationale they offered only unargued assertions, most of which are untrue. The policy runs out way ahead of historical evidence and ethical reason and suggests a shocking lack of due diligence.

Since early 2024 a group of concerned church members and citizens have publicly criticised the Commissioners, in the hope of persuading them to think again. In addition to myself, these include:

Dr Alka Cuthbert-Seghal, Anglo-Indian director of the anti-racist advocacy group, Don’t Divide Us;

Richard Dale, Emeritus Professor of International Banking at Southampton University;

Lawrence Goldman, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Oxford;

Lord Tony Sewell, former chairman of the Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, dual citizen of the UK and Jamaica, and descendant of African slaves;

Robert Tombs, Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Cambridge; and

Charles Wide, KC, former Old Bailey judge.

In February 2025, myself, Wide, and Seghal-Cuthbert published The Case against Reparations: Why the Church Commissioners for England must think again (Policy Exchange: https://policyexchange.org.uk/publication/the-case-against-reparations/). A few months later Independent responses to claims criticising the historical basis of the Church Commissioners’ research quietly appeared on the Church of England’s website. One of the two respondents was Richard Drayton, whose claim to ‘independence’ is doubtful, given his involvement in Project Spire since July 2023. In July, Biggar et al. rebutted the Independent responses in A critical commentary on Church Commissioners’ historic links to African chattel enslavement on the History Reclaimed website.

Since then, the Church Commissioners have offered no ethical justification at all for their policy. Instead, they have dismissed their critics (without ever naming them) as acting in bad faith through deliberate disinformation, and they have declared that they will not respond to arguments that African descendants find ‘offensive’. But suppose it’s the truth that offends?

This issue is not going away. Questions are being asked in Parliament. If the Church Commissioners keep on digging, they risk a major national scandal. Reputations may not survive it.

What follows is an abbreviated and edited version of Chapter 12 of my book, Reparations: Slavery and the Tyranny of Imaginary Guilt, which was published by Swift Press on 25 September.

Part I

In November 2023 the Church Commissioners of England, the body responsible for administering the property assets of the Church of England, committed the church to deploy an initial £100 million of those assets to establish an investment fund, which will support communities “affected by historic slavery”. This commitment was made in response to the discovery that the Queen Anne’s Bounty, an 18th century forerunner of the Church Commissioners’ endowment devoted to supplementing the income of poorer clergy, had “links” with African chattel enslavement.

A document entitled, Oversight Group Recommendations: Healing, Repair and Justice, explains: “The immense wealth accrued by the Church Commissioners has always been interwoven with the history of African chattel enslavement.... [which] was central to the growth of the British economy of the 18th and 19th centuries and the nation’s wealth thereafter”. Now, the commissioners acknowledge a “strand of complicity in an abominable trade that still scars the lives of billions ... the cruelty of a multinational white establishment that deprived tens of millions of Africans of life and liberty ... has continuing toxic consequences ...”. Hence, the need for the Church to make reparations, repairing the “damage caused by past injustice which continues via present injustice”.

Part II

Observe how the rationale given for making reparations depends on a set of unargued assertions: that the Church’s “immense wealth ... has always been interwoven” with enslavement; that slavery was “central” to Britain’s economic growth and prosperity; that slavery was perpetrated by a “white establishment” upon Africans; and that today’s descendants of slaves two centuries ago continue to suffer the effects of ancestral enslavement.

Every one of these claims, however, is either dubious or false. The contribution of slave-trading and slavery to Britain’s economic development is a highly controversial matter, but most economic historians reckon it somewhere between marginal and modest. Slavery was perpetrated on black Africans by other black Africans long before it was perpetrated by a ‘white establishment’. And between abolition in 1834 and the present day, all sorts of other causes have intervened to complicate, dilute, and even reverse the effects of slavery.

As for the Queen Anne’s Bounty, it was barely involved in slave-trading at all. The story is this. According to Robert Tombs and Lawrence Goldman, the South Sea Company was established in 1711 “to absorb short-term unfunded government debt by converting it into company shares that could be traded on the stock market. In return, the government paid interest to the South Sea Company which then went to investors”. Two years later in 1713, when war with Spain ended in the Treaty of Utrecht, the company acquired the privileges of trading a certain number of slaves into Spanish colonies, as well as importing a ship’s worth of merchandise per annum. From that point on, shareholders could profit in two ways: through a government annuity paid on the shares and through commerce with Spanish colonies. The latter comprised only a very small part of its financial operations. It was also very uncertain, being frequently interrupted by war in 1718-20, 1727-29, and 1739, after which it ceased entirely. And it proved unprofitable.

In 1720 the Queen Anne’s Bounty converted some of its holdings of short-term government securities into South Sea shares, resulting in a serious loss. In 1723, since many shareholders wanted to avoid participating in the Company’s trade altogether, the existing shares were formally divided into ‘annuities’ and trading stock (‘shares’). Preferring to invest in the former alone, the Bounty sold most of the latter five years later and all of them by 1730. Richard Dale, author of The First Crash: Lessons from the South Sea Bubble (2004), has commented:

If the Bounty managers had wished to benefit from the slaving business, they would have invested in the Company’s shares; but, with one minor exception in 1720—when the slave trade was shut down owing to war with Spain—they chose to avoid the risks and rewards of the commercial business and invested, instead, in what were essentially government-backed debt instruments.

He continues:

The [Church] Commissioners conclude that “. . . a significant portion of the Bounty’s income during the 18th century was derived from sources that may be linked to transatlantic slavery, principally interest and dividends on South Sea Company annuities”. This conclusion is misleading on several fronts. First, no investor in the South Sea Company benefited financially from the slave trade, since it was consistently loss-making. Second, the Church Bounty did not even stand to benefit from the trade, because it declined to buy shares in the Company. Third, the investments that it did make, in South Sea annuities, represented, at one remove, claims on the Government which had no connection with the trade in slaves. Finally, it is grossly misleading to suggest, as the church report does, that all South Sea investors were consciously investing in slave-trading voyages.

However, it is true that the managers of the Queen Anne’s Bounty did hold onto trading stock after trade resumed in June 1721, selling nearly all of them by 1729 and all by 1730. Goldman and Tombs comment:

However, while the connection of the Bounty with the slave trade was reprehensible and a proper cause of regret, it was certainly not the source of “a historic pool of capital”. The South Sea Company never made any profit from slave trading, and the Bounty did not derive any income from slave trading during the brief period when it held shares in the Company. On the contrary, its 1720 investment in shares made a disastrous loss, equal to 14 percent of its total portfolio.

Part III

In addition to revenue from the South Sea Company, the Queen Anne’s Bounty also comprised benefactions. According to The Church Commissioners’ Research into Historic Links, these generated around 14% of the Bounty’s income in the 18th century. Its analysis of benefaction registers between 1713 and 1850 has led it to conclude that “the proportion of benefactions derived from individuals who were considered to have a very high (8%) or high (22%) likelihood of potentially being linked to the transatlantic trade in enslaved people was overall about 30% of all benefactions that were received by Queen Anne’s Bounty”.

Note, however, the highly speculative basis of the claim: “likelihood … potentially”. The factors allowed to determine likelihood included simply “being active at the time of the South Sea Bubble; involvement in politics (including being a member of the House of Lords); being linked to cities that were heavily involved in transatlantic slavery such as Bristol, Liverpool, London and Manchester; being linked to industries that relied on transatlantic slavery such as cotton, copper or iron; and having naval connections”. It would have been perfectly possible to have had every one of these associations and yet to have had no involvement in slave-trading at all.

In one section The Church Commissioners’ Research explains that its calculations include benefactions that “appeared” to have been made by relatives or descendants of Edward Colston. A Bristol merchant, Colston was, for twelve years from 1680 to 1692, a member of the Royal African Company, which traded in slaves from West Africa. In some cases, it is clear that the benefactions “were derived directly” from Colston. But not all: “it is possible”, for example, “that the monies provided by Alexander Colston were his own and were not derived from the transatlantic trade in enslaved people”. However, even where benefactions did derive directly from Colston, it is impossible to know how far they included proceeds from slave-trading—or whether they did at all. After all, Colston lived for 84 years and was engaged from the age of 18 in a wide range of commercial activity, including trade in wine, oil, textiles, and cod from Newfoundland to Naples.

In the end, then, what do we know about the involvement of the Bounty in slave-trading? We know that it bought South Sea Company shares during a period, when, thanks to war, the company was not involved in trade with Spanish colonies at all; that it retained some trading stock from the end of the war in June 1721 to 1730; that it made no money out of it; that it chose to divest itself of that stock over those nine years; and that some benefactions might have derived from profits made from slave-trading. We do not know whether benefactions loosely ‘linked’ to slave-trading actually derived from it. Nor do we know whether benefactions from merchants, who were certainly engaged in slave-trading, were based on profits made there as distinct from the many other commercial ventures they were engaged in.

Notwithstanding this, the Church Commissioners have put their signatures to documents that assert that “the transatlantic slave economy played a significant role in shaping the … Church we have today” and that “[t]he immense wealth accrued by the Church Commissioners has always been interwoven with the history of African chattel enslavement”. Both these statements run out boldly ahead of the meagre evidence.

Part IV

We have observed how several important things that the Church Commissioners do say are not true. Now, we need to observe an important thing that they do not say. They make no mention at all of Anglican involvement in the dogged, half-century-long campaign to abolish the slave-trade and slavery; or of the fact that the British were among the first peoples in the history of the world to abolish them; or of Anglican involvement in the subsequent century-and-a-half of British imperial endeavour to suppress slavery worldwide from Brazil to New Zealand.

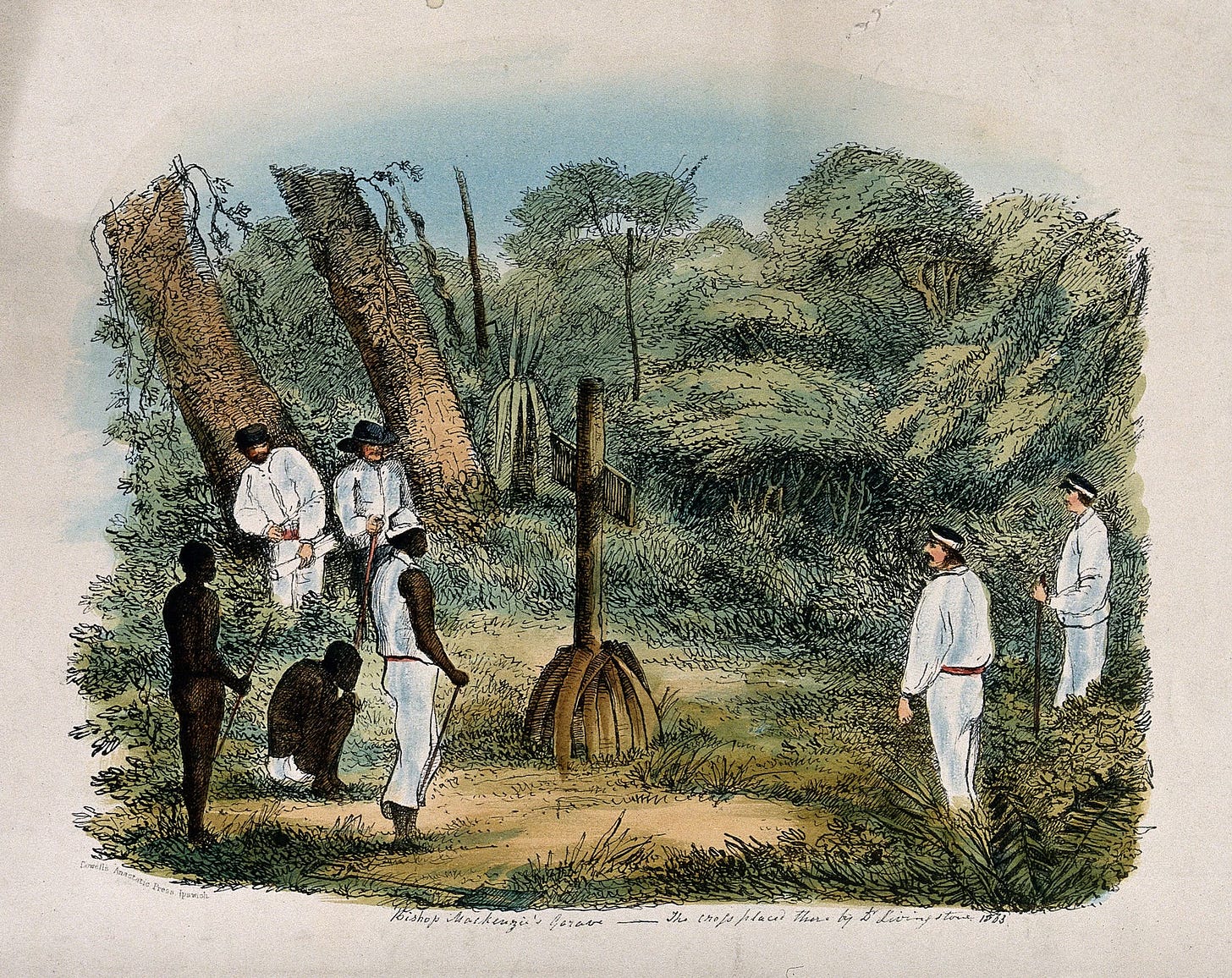

It is particularly egregious that the Church Commissioners should have failed to take into account all those Christian missionaries who, following David Livingstone, risked—and sometimes spent—their lives endeavouring to end the slave-trade in Africa. Among them was the Anglican bishop, Charles Mackenzie, who died horribly of blackwater fever in what is now Mozambique in 1862 at the age of 37.

In a sermon preached in Christ Church Cathedral, Zanzibar on 12 May 2024, the then Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, while acknowledging the missionaries’ fight against slavery, went on to criticise them for treating Africans as inferior and to confess that “we must repent and look at what we did in Zanzibar”. This is odd, since what the British did in Zanzibar during the second half of the 19th century was to force the Sultan to end the slave-trade. As for racial prejudice among missionaries, Alexander Chula, who lived and taught in Malawi for three years, writes this: “I am curious to know who exactly the former Archbishop had in mind. Mackenzie’s successors gave everything they had to the region, and their graves litter Malawi, still venerated today. They committed to sharing the lives of local peoples and … approached their cultures with a curiosity and respect seldom matched by Western visitors today. The imputation that they treated Africans as inferior dishonours men who died precisely because they considered Africans as worthy of that sacrifice as anyone”.

Part V

Finally, we should observe how, apart from the forensic analysis of the Queen Anne’s Bounty, none of the Church Commissioners’ assertions is supported by a methodical ethical argument. But such an argument is surely needed. The moral duty to repent of wrongs we have done and to repair them as far as possible is Christian common sense. And while we cannot exactly repent of wrongs other people have done, if we have benefitted from their wrongdoing, we do have a responsibility to try to correct it. So far, so straightforward. Things become much more complicated, however, the more time elapses between the past wrong and the present. The onerous effects of the original wrong become mixed up with—and maybe ameliorated by—other effects, so that the descendants of victims do not suffer as the victims themselves did. And historic beneficiaries of the wrong may already have invested time, money, and lives in trying to correct it.

Instead of offering a carefully reasoned ethical justification, the Church Commissioners charged an ‘Oversight Group’ with working out a plan for implementation, whose recommendations they then rubber-stamped. But this ‘Oversight Group’, while sporting “a great diversity of skills and backgrounds”, seems to have contained no significant intellectual diversity at all. They all shared the same basic historical, moral, and political assumptions, which they saw no need to subject to genuinely critical testing. If this appearance is true, the Commissioners failed to discharge their duty as trustees, since according to the Charity Commission, trustees should “critically and objectively review proposals and challenge assumptions in making decisions…. Trustees who simply defer to the opinions and decisions of others aren’t fulfilling their duties”. Such a failure of due diligence—on the part of Church Commissioners, no less—is shocking.

As ever, a thorough, even-handed, fearless statement of historical fact and, equally, of our lack of knowledge of the past. And also of the ethics of how one should arrive at a decision about the past, and how much we should be bound by it. Brilliant!