Slavery: What's the Matter with 'Whataboutery'?

We need to be clear about slavery both inside and outside the West.

I

A common criticism made of my arguments in defence of the British Empire and against Britain’s paying reparations for historic slavery is that they indulge in ‘whataboutery’. I say ‘criticism’, charitably. For, since the critics seldom bother to explain what they mean, it usually amounts to nothing more than a summary dismissal. Since all ‘we’ right-thinking people know how feeble such an argument is, it suggests, no explanation is necessary.

An exception to this, however, has been made by one vigilant critic, who anxiously rushed out a condemnation of my latest book, Reparations: Slavery and the Tyranny of Imaginary Guilt, within days of its publication. In this, he does pause to explain what he thinks is wrong with ‘whataboutery’, writing as follows:

Biggar’s ethical case rests on two observations. The first is that other people practised slavery too. As Biggar puts it in his Daily Mail article, “The humiliation and cruelty of British slave-trading and slavery was unique neither in kind nor degree. Many, many other peoples did similarly lamentable things, not least Africans and Arabs, and for a much longer period of time”. I am not an Anglican theologian so maybe I am missing something, but my lay understanding of the Christian idea of sin is that it is an affront to God in its own right, regardless of how many others commit it. Biggar’s observation seems relevant only if one believes that the more people commit a crime the less it matters…. Whataboutery seems to me a very fragile ethical edifice upon which to build an anti-reparative argument.

Since the second ‘observation’ allegedly supporting my ethical case is not in fact mine at all—my critic derives it from the title of Philip Hensher’s laudatory review in The Spectator, “What has the reparations movement ever done for victims of modern slavery?”—I shan’t address it. Which leaves my case apparently standing on one leg only: the fact that other people also practised slavery. Except that, as any careful reader of my book will know and as will become clear in what follows, it rests on a lot more than just that. (Rare is the critic who isn’t so blinded by bigoted hostility that he is able to resist misrepresenting what I write. This critic is not so rare.)

II

Nonetheless, my critic is to be commended for attending to the ethics of my argument, which other historians invariably overlook. And he is quite right to think that (whether one is a Christian or not) what is wrong is not made less wrong just because lots of people do it. Of course not. That, however, is not the point of putting the involvement of some British people in slavery in its proper, historical context.

At its most general, the point of contextualisation is to make the self-righteous 21st century moraliser get off his moral high horse and begin to appreciate the strange, even disturbing difference of the past, by contemplating the universality of a practice that we now take for granted as gravely wrong. How come it was so prevalent? How come so many were so unenlightened for so long? Is it just because we ‘progressive’ folk are naturally more enlightened and virtuous than ‘primitive’ people in the past? Could it possibly be because their circumstances were so very different from our own? Could it sometimes be that, not privileged with our accustomed wealth and security, when they defeated enemies in battle, could not afford to let vanquished warriors walk free, and lacked expensive systems of long-term detention, our ancestors had a stark choice between slaughtering prisoners or enslaving them. Or could it be that, sometimes, survival required the forced labour of others—as on the coast of the North-West Pacific, where processing the quantity of salmon needed for subsistence far exceeded what the labour of women could supply? Besides, how come we are so enlightened? Could it be that it’s because we are the (ungrateful) beneficiaries of the lessons that our ancestors had to learn the hard way?

The most general reason for putting British involvement in slavery in context is to humble the 21stcentury judge and to improve the wisdom of his judgement, by making it attentive to circumstances and the moral difference they often make.

III

A second, particular point is to make clear that British slavery was, while wrong, equally wrong; and while often very brutal indeed and more brutal than some, not uniquely so. In my book, I give illustrations of the horrifically cruel lengths to which British enslavers could go. I do not avert the readers’ eyes from that. But I argue that the cruelty of Barbary corsairs towards their white, European slaves was sometimes equally horrific.

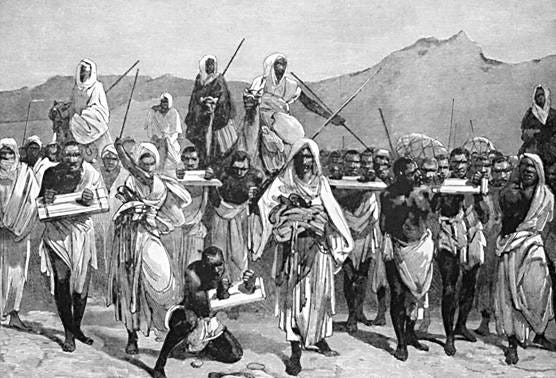

Had I read Justin Marozzi’s Captives and Companions: A History of Slavery and the Slave Trade in the Islamic World (2025), I could have added another example. For centuries pre-pubescent African boys were regularly raided and enslaved by other Africans and then sold to Arab traders. Many of them were made ready to serve as eunuchs. Being ‘made ready’ involved having the testicles (and sometimes penis, too) removed with a razor, a wooden catheter inserted, and boiling oil poured over the wound to cauterize it. If the catheter did not allow the passing of urine, the child died, in agony. A mid-nineteenth century French witness reckoned that, every year, it took 38,000 boy-slaves from the Sudan to produce 3,800 eunuchs. In other words, almost 90 per cent of them died in the process.

Can we say that they were nonetheless better off than African men and women who perished in the horrendous conditions of the sea voyages from West Africa to the Americas, or those who were worked to death in the sugar plantations of the West indies? I don’t think so.