The Canadian Atrocity Myth

Since the first alleged discovery of a mass grave of native Canadian children at a school in British Columbia in 2021, the narrative that Canada’s Indian Residential Schools—and by extension Canada’s colonial history—occasioned atrocity and genocide has become public orthodoxy in Canada. It has excited arson and vandalism against over a hundred Christian churches, the toppling of statues of Canada’s founding premier, John A. MacDonald, and the reparative spending of thirty billion dollars of public funds. It’s also a narrative that Chinese diplomats have been quick to exploit to deflect Canadian criticism of its own ‘genocidal’ treatment of the Muslim Uighur people. Yet the narrative is false.

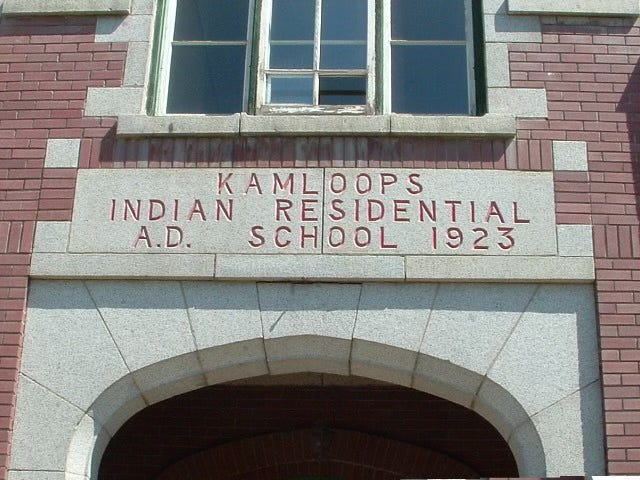

When in February Dallas Brodie, a member of the legislature of British Columbia, declared on X that the number of burials of missing children confirmed at Kamloops Indian Residential School was “zero”, her fellow Conservative, Áʼalíya Warbus, condemned her for “questioning the narratives of people who lived and survived … atrocities”. And the president of the Métis Nation of BC, Walter Mineault, responded that “the residential school experiences … were not ‘objective truths’ for Métis people but their lived experiences”.

Well, no experience is raw; it’s always interpreted. And interpretations are based on perceptions that can be mistaken or distorted. To claim that only white people can misremember and fabricate would be racist. Racial equality requires, therefore that we test indigenous claims of ‘lived experience’ against objective evidence, to find out if they’re true. Because they might not be.

And yet, in what amounts to a national scandal, the ‘atrocity’ tale prevails. Why? One reason is that positive witness from former pupils has been suppressed…

So, what is the evidence about Canada’s residential schools?

On Kamloops, Brodie was quite correct: no graves of missing children have been discovered, because no disinterment has been attempted almost four years after the claim was first made. What we do know is that the alleged ‘mass grave’ is the site of a century-old septic system, whose trenches lined with clay tiles match the direction and depth of the suspect “sub-surface anomalies” identified by ground-penetrating radar in 2021.Apart from indigenous say-so, there is no evidence of hidden graves—either in Kamloops or anywhere else in Canada.

More generally, is it true that the residential schools were forced on indigenous people? For most of their history, no. The idea originated with Indian leaders in the 1830s, who recognised the need of kids in remote areas to adapt to the new world that had unavoidably come upon them, by learning English and agriculture. As late as the 1920s indigenous bands in Alberta and in the Northern Territory’s district of Keewatin were lobbying for more such schools. Parents had to apply in writing for their children to attend, since boarding was over three times more expensive than day school. And fifty per cent of Indian kids left both day and residential school after Grade 1. In short, admission was only at parental request and exit was at will.

It is true that in 1920 the authorities acquired the legal power to compel attendance, but that’s only because all Canadian kids, regardless of ethnicity, were required to go to school. And that coercive power was used sparingly. However, by the 1940s, the residential schools had changed their main function from being educational institutions to being care-homes for native children, who had been removed from abusive, dysfunctional, or simply overcrowded homes for the sake of their own welfare—sometimes with parental consent, sometimes without it. That must be the period to which most contemporary testimony refers. In which case, how far memories of childhood unhappiness are due to oppressive schools, and how much to disturbed homes, must surely be a moot point.

The widespread condemnation of the residential system, however, is not confined to its last half-century. It’s commonly believed that, out of a total of up to 150,000 pupils between 1883 (when the federal government started to fund residential education) and 1998 (when the last residential school closed), over 4,000 died, because of culpable neglect, abuse, or murder. Where does that figure come from?

Its basis is the number of deaths given in the 2015 final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (TRCC): 3,201. Yet, the report actually identifies only 423 named children who died on the premises of a residential school. And it admits that some, at least, of a further 409 unnamed kids may be duplicates of them. It also admits that in 1,391 cases (43.5 per cent) the location of death is unknown, yet it assumes that all the former pupils who died within one year of leaving, did so because of poor conditions in their schools.

However, records reveal that some of these died because of accidents suffered, or tuberculosis contracted, on their home reserves. TB was a disease endemic in indigenous populations before the arrival of Europeans, and a very high proportion of Indian kids arrived at the residential schools already infected with it, because of poor living conditions at home. Even now, indigenous communities in remote areas suffer an extraordinarily high incidence of it: among non-native Canadians the current rate is 0.6 per 100,000, while among Indigenous Canadians it is 24, and among the Inuit, 170. To what extent the schools inadvertently exacerbated the problem through overcrowding and poor ventilation, before reforms were made in response to Dr Bryce’s reports in 1907 and 1909, is impossible to determine.

The TRC’s figure of 3,201 was inflated to 4,117 in June 2021 by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation at the University of Manitoba, which claimed that the deaths had been caused by malnourishment and disease in the schools and amounted to “atrocities”. Yet, again, that figure includes pupils who died up to a year after leaving a residential school, no matter what the cause of death. At least one was murdered months after his departure at the age of 19. What’s more, it also includes the names of any pupil whose family simply wanted their attendance memorialised, including one who died at the ripe old age of 85.

So, how many inmates of the schools died on the premises? Assuming no duplication of the named and unnamed recorded deaths, the only firm figure is 832 or 0.55 per cent of the total of 150,000 pupils. (The death rate for non-indigenous children throughout Canada in the 1880s was 2.5 per cent.) How many Indian kids subsequently died because of poor conditions in the schools? We don’t know. But we do know that many of them died from other causes or would have died from TB anyway. The claim that over three or four thousand pupils were deliberately killed or died through culpable neglect—and that their deaths amount to an ‘atrocity’—is patently false, lacking any evidential basis whatsoever.

Yes, there is evidence of some sexual abuse of minors by adults at the residential schools. While lamentable, however, such misconduct is not confined to history. It happens now, and it will happen tomorrow. Sin can be contained; it can’t be abolished—not even in Canada. As for the scale of the abuse, again, we don’t know. J.R. Miller, whose measured 1996 book, Shingwauk’s Vision, is the standard history of the residential schools, observes that much of it occurred between pupils. And records in the Department of Indian Affairs report the difficulty of preventing girls and boys creeping into each others’ dormitories, implying that some of it, at least, was consensual.

Ok, but what about the ‘racist’ repression of native languages? One of the main aims of the schools was to have indigenous kids learn English, so that they could participate fully in the new Anglicised society that was enveloping them, and we all know that the most efficient way to acquire a new language is to be totally immersed in it. That said, there do appear to have been cases where the prohibition of native language-speaking was excessive. Yet, we also know that there were schools where teachers themselves took the trouble to learn native languages and permitted pupils to speak them outside of the classroom. The record falls a long, long way short of systematic cultural ‘genocide’.

Finally, there is the charge of inadequate funding—but if anyone was to blame for that, they resided in Ottawa, not in the schools themselves. J.R. Miller, for one, is scathing about tight-fisted government bureaucrats. Yet, elected governments and civil servants are more sensitive than academics to the fact that public funds and borrowing-capacity are not infinite, and that more money spent in one direction may well mean less spent in another. Moreover, we do need to remember that governments in the past had nothing like the resources they do now. For example, today in the UK, the government has the equivalent of almost 46 per cent of GDP at its disposal; in 1900, it had only 8 per cent. In the 1870s, the US government spent more on fighting frontier wars in its Wild West than the whole of the Ottawa budget. Nonetheless, in 1882 John A. MacDonald’s government spent more on Indian affairs than it did on defence, the administration of justice, or civil government. Was Ottawa unreasonably stingy in its expenditure on residential schools because of racist prejudice? Not obviously.

So, when all is said and done, what do we know about Canada’s residential schools? We know that conditions were invariably poor by our standards, but then so they were everywhere in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—and they were often worse in the homes from which indigenous pupils came. We know that the crowding of already diseased children together and the lack of ventilation probably, although inadvertently, increased the spread of TB, until reforms were made. We know that some repression of native languages was unreasonably strict and some sexual abuse of minors by adults took place. And we know that the compulsory removal of kids from dysfunctional families was distressing, notwithstanding the benevolent intention. There is, however, no firm evidence that indigenous kids died in the schools in excessive numbers from culpable negligence. And there is no evidence at all of mass murder.

And yet, in what amounts to a national scandal, the ‘atrocity’ tale prevails. Why? One reason is that positive witness from former pupils has been suppressed, while negative testimony has been solicited. Miller observes that, even back in the 1990s, a sensation-seeking media had an appetite only for stories of abuse. And while the body of the TRCC’s 2015 report contains a lot of positive testimony, its summary volume permits it only a brief appearance, before dismissing it with the observation that ‘survivors’ found it distressing to hear. This imbalance of testimony has surely been exacerbated by the subsequent compensation system that offered significant sums of money to any former pupil claiming to have suffered abuse, without subjecting the claim to much or any kind of testing. Given universal human nature, it is a practical certainty that many such claims were fabricated and that the negative bias of testimony was further exaggerated.

Beyond that, blame for the tyranny of a false public orthodoxy about the residential schools rests with representatives of the TRCC and academics, who know full well that the data is being misrepresented and yet have failed to offer any correction. It lies with journalists and editors who have declined to ask questions. It lies with politicians who have tied their careers to the mendacious narrative. And, most of all, it lies with those who have—shockingly—persecuted sceptics and critics to the point of destroying their reputations and careers, even (like Leah Gazan, MP) pressing for the totalitarian criminalisation of ‘denialism’.

Nonetheless, the truth is wrestling its way inexorably to the surface. The past four years have seen three books appear, each of which dismantles the ‘atrocity’ fabrication: Rodney Clifton and Mark DeWolf’s 2021 From Truth Comes Reconciliation, Chris Champion and Tom Flanagan’s 2023 Grave Error, and my own 2023 Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.

And last month the plight of silenced dissidents in Canada received a major uplift with the launch of the country’s own Free Speech Union (FSU). In the UK, in just over sixty months, the original FSU has attracted over 25,000 subscribing members, has proven very effective in publicly exposing and fighting cases of free speech repression, and is now sufficiently bold and well-resourced to take the UK Government itself to court.

The time is coming in Canada when the Warbuses, Mineaults, and Gazans—and not the Brodies—will find themselves called to account. It can’t come soon enough.

A version of this article was published in Canada’s National Post.