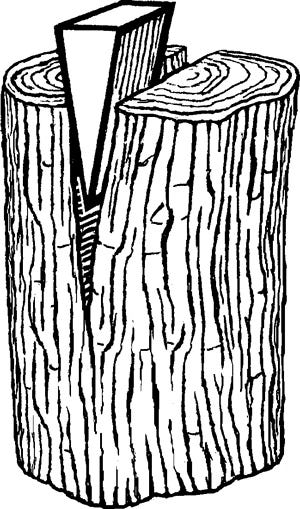

The Thin Edge of the Wedge

The Lords must stop legalised suicide.

In June 2025 draft legislation to legalise assisted suicide, the Terminally Ill Adults (End of Life) Bill, completed its first run through the UK’s House of Commons, and was formally introduced to the House of Lords on the twenty-third day of that month. On 12 September 2025, the Lords began two days of the Second Reading of the bill, when issues of principle are discussed. After the first day and in advance of the second day of debate, on 19 September, Nigel was commissioned to write the following article for the Daily Telegraph:

When Kim Leadbeater’s Terminally Ill Adults bill to legalise assisted suicide for the dying reached the House of Lords last Friday, peers faced a dilemma. On the one hand, they heard the persistent concern of advocates for the disabled and several Royal Colleges about the risks of abuse and corrosion of humane social norms that legalisation threatens.

On the other hand, their compassion was aroused by stories of individuals suffering grievously, whose plight couldn’t be assuaged by palliative care, and of those helping them find relief through suicide having to endure police investigation. The bill, urged Lord Falconer of Thoroton, would resolve this intolerably cruel situation.

“Compassion is a virtue. But it needs to look in more than one direction and distribute itself equitably. For compassion that takes impatient and imprudent risks with the lives of the vulnerable is no virtue at all.”

Except it wouldn’t. By limiting assisted suicide to the terminally ill, the bill excludes those who aren’t dying but are still suffering grievously. And it would still bring the police to the door of those assisting them commit suicide. So, anyone who supports the bill, intending that terminal illness should remain a condition of eligibility, accepts that some people, tragically, have to suffer grievously—because the social dangers of wider access are just too great. But if this situation is tolerable, why is the current status quo not so?

Of course, many supporters view terminal illness, not as a permanent limitation, but only as a tactical beachhead for later strategic expansion. Which it would be. Because although the bill’s text doesn’t mention the relief of ‘unbearable suffering’ or respect for ‘autonomy’, no one reading Hansard can doubt that those are the principles driving legislative intent.

So, after the law has approved assisted suicide for the terminally ill, the argument would soon be heard—probably with appeal to Articles 8 and 14 of the European Convention of Human Rights—“Why the unfair discrimination? If autonomy for the terminally ill, why not also for the chronically ill? And if the physically ill, why not also the mentally distressed? Don’t they suffer unbearably, too?”.

Several speakers in last week’s debate asserted the individual’s ‘fundamental right to autonomy’ as an axiom, turning a completely deaf ear to warnings of legalisation’s social dangers. Were axiomatic autonomy to dominate the field, the end of its logic would be the right to assisted suicide for all sane, mature adults, presumably as young as 18 year-olds.

If we were serious about reducing the quantity of human suffering, we wouldn’t be focussing on legalising assisted suicide, reckoned to be accessed by a maximum of 7,500 people within a decade. Rather, we’d focus on the universal provision of good palliative care, which more than 100,000 citizens every year need, but lack.

Indeed, if Parliament were to pass the Leadbeater bill before securing that, it would create a grave inequality of autonomies. For, while some—typically more privileged—would have a choice between decent palliative care and assisted suicide, others—typically poorer and less white—would have to choose between grievous suffering and killing themselves. That’s why in last November’s Focal Data poll of over 5,000 people, two thirds wanted the provision of social and end-of-life care “sorted out first” before any thought is given to permitting assisted suicide. That’s also why in its 2012 report the Demos Commission, chaired by Lord Falconer himself, stipulated as an “essential” precondition of legalisation, the universal provision of “the best end of life care available”.

Compassion is a virtue. But it needs to look in more than one direction and distribute itself equitably. For compassion that takes impatient and imprudent risks with the lives of the vulnerable is no virtue at all.

Notwithstanding all this, peers have been warned that the ‘people’ in successive polls overwhelmingly supports the legalisation of ‘assisted dying’. That’s true. But many of them don’t understand what they’re supporting. The Focal Data poll also revealed that 40 per cent thought that ‘assisted dying’ referred to hospice treatment or the right to refuse treatment, not to assisted suicide. What’s more, the popular majority doesn’t always get it right. For decades the popular will has supported the return of capital punishment, and for decades Parliament has wisely resisted it.

Peers have also been told that their lordships mustn’t defy the will of the elected House of Commons, which passed the Leadbeater bill at its third, conclusive reading. However, the Lords are not bound to pass a Private Members Bill, which wasn’t in the Government’s General Election manifesto. Moreover, during its passage through the Commons, confidence in the bill’s safeguards against abuse plummeted. Between its Second and Third Readings, its majority halved and had a mere 12 MPs changed their votes from Yes to No in the final vote, the Lords wouldn’t be discussing it at all.

So, peers shouldn’t let themselves be deflected from their public duty to make rigorous examination. They should begin, this coming Friday, by voting for Baroness Berger’s amendment, which would route the bill into a select committee, to hear from professional bodies about safeguards and to press ministers about how exactly an assisted suicide service would operate. Only this can compensate for the Commons’ poor scrutiny of the bill, which, given its subject-matter, the Lords’ Select Committee on the Constitution deemed “especially concerning”.

In the course of the two days of debate, an estimated 53 peers spoke in favour of the bill, and 103 against. At the end of the second day’s debate on 19 September, the House of Lords unanimously agreed to route the TIA bill into a select committee, which will report by 7 November.

Bravo!