Why I am a Conservative

“IT’S TIME you came off the fence, Nigel.” So said conservative philosopher Sir Roger Scruton, turning half-around as he walked away from my Oxford front-door one sunny afternoon in 2016. He’d come to look at Christ Church’s wine-list (and was leaving impressed). But we’d also talked politics. I’d told him that I preferred not to be boxable, maintaining room for manoeuvre. “Whether I’m conservative or liberal, Roger,” I said, “depends on (a) what I’m talking about and (b) whom l’m standing next to. It all depends”. At the time, I subscribed to both the Guardian and the Times.

Scroll forward six years to June 2022. Grown depressed with what Peter Hennessy once described as its relentless “litany of complaint”, I’ve cancelled the Guardian. I’m on the House of Lords’ riverside terrace, being lunched by my long-time mentor, Richard Harries, formerly bishop of Oxford, now Baron Harries of Pentregarth. Richard leans over the table and counsels me, “Don’t get labelled ‘conservative’, Nigel. Conservatives don’t believe in anything. They’re just pragmatists”. I mumbled a non-committal response. But I thought to myself, “I don’t doubt there are many conservatives who believe in little beyond low taxes and deregulation, but I’m not one of them”. Then I heard my next vocation speak: “It’s time to nail your colours to the mast and explain what a richer conservatism looks like”.

So, in this season of enforced political Lent, when Tories are ruing their recent sins of commission and omission, and wondering what sort of repentance might hasten their party’s resurrection, I offer my own confession of what a conservative should be. But while others divine the entrails of polls for guidance on vote-winning policies, I step back to reflect on the deeper springs of a conservative point of view.

Gratitude and God

That is what the coronation ritual embodies, when the monarch gets onto his knees to receive the crown—the symbol of political authority—not from below, but from above. Not from the fickle people, but from the constant God.

I DIDN’T so much jump, as ease off the fence. I was also somewhat pushed. But the direction of travel had been set early on. I was a child in the sixties, but not of them. I never trusted the frivolous trashing of the past. While I laughed at Monty Python’s mockery of Battle of Britain pilots, made ridiculous with their plummy accents and handlebar-mustaches, my laughter was uneasy. After all, just thirty years before, such men had risked their twenty-something lives to save the nation from Nazism, some of them burning alive in their cockpits. So, while my elder brother (sadly, long dead) was swallowing hashish-filled condoms for smuggling onto flights from Nairobi to Glasgow, I performed my first act of conservative rebellion: while churches were beginning to show more seats than bums, and to the bemusement of my churchless parents, I converted to Christianity.

A main reason was my attraction to the Christian vision of human life as a moral adventure, made heavy with meaning because so much is at stake for good or ill. It endows our little lives with significance by relating them to things whose lasting value we receive as given: caring for others’ well-being, doing justice, maintaining integrity, knowing the truth, preserving what’s beautiful. Seen thus, human dignity derives from the service of objective ‘goods’. It’s given from above, so to speak, not invented from below.

That’s why I support the conservation of Britain’s traditional, mixed constitution. A good political constitution certainly needs a part where rulers are made sensitive to those they rule—an elected legislature whereby the people can hold their government to account, stop it in its tracks, and even eject it. It needs a democratic element.

But it needs more than that. The people can be corrupt and popular majorities can be seriously unwise—after all, Hitler was elected by due democratic process. Moreover, popular election can’t guarantee a body of legislators all the expertise it needs. At some recent point, for example, the House of Commons didn’t contain a single medical doctor. So, a healthy political constitution needs a way of importing expertise into the legislature—by appointment to an unelected Upper House. It needs an aristocracy of wisdom.

It also needs a monarch who symbolises the accountability of the whole nation— king and people, rulers and ruled, government and opposition—to given values and principles of justice that are not the passing creatures either of royal fiat or of majority vote. That is what the coronation ritual embodies, when the monarch gets onto his knees to receive the crown—the symbol of political authority—not from below, but from above. Not from the fickle people, but from the constant God.

War and Peace

GROWING UP in the shadow of the Second World War—I arrived only ten years after its end—imbued me with the conviction that violent force is sometimes necessary to fend off very great evil. My mild-mannered father was transported from the gentle Galloway hills of Scotland to the war-torn Apennines of northern Italy, and I have climbed the hill where, in October 1944, he found himself trapped in no-man’s land as a stretcher-bearer. Though spared his fate, I’ve read enough to know of war’s horrors, second-hand.

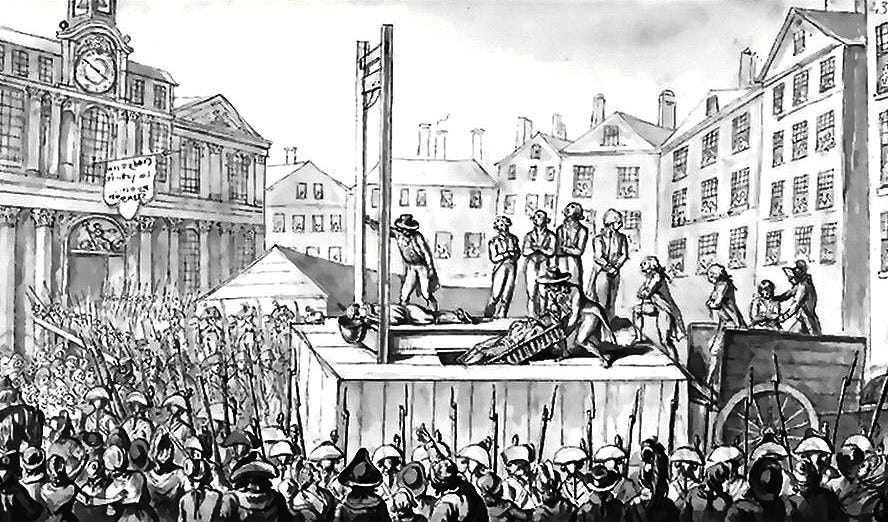

Nonetheless, I continue to think that the use of hard power is sometimes—lamentably, tragically—necessary. So, in 2013 I published a book about the ethics of violent coercion, drawing on the sixteen-hundred-year-long Christian tradition of ‘just war’ thinking. Provocatively titled, In Defence of War opposed itself to “the virus of wishful thinking”, borrowing a phrase from Michael Burn’s extraordinary 2003 autobiography, Turned toward the Sun. But while Burn was referring to his naive hope in the 1930s that Hitler would turn out okay, the virus I had in mind was pacifism—the idea that war is always and everywhere morally wrong—and the ‘progressive’ aspiration to abolish war through international law. If war invariably causes dreadful destruction, peace can permit it. Not going to war in 1994 was good for Britons, but not so good for the Tutsi in Rwanda: our staying at peace left the Hutu at peace to slaughter 800,000 of them. Peace, like war, is morally complicated.

Accordingly, I supported British military intervention for humanitarian purposes in Kosovo in 1999, Afghanistan in 2001, and Iraq in 2003. While each of these was flawed, none has made me abandon the possibility of morally justified military intervention. But what they did impress on me was both the importance and the morality of engaging the national interest. There’s nothing necessarily immoral about this, since nations have morally legitimate interests that it’s the primary duty of national governments to serve. So, while saving foreign peoples from grave political evils would be a good thing to do, it’s perfectly reasonable for citizens to ask their rulers why their uniformed sons, daughters, and siblings should be put in harm’s way over there, in some distant part of the world. This point was well made in 1796 by Edmund Burke, who was advocating British military intervention in France to stop revolutionary atrocities there. Challenged to explain why he didn’t also advocate intervention in equally deplorable Algiers, he replied, “Algiers is not powerful; Algiers is not our neighbour; Algiers is not infectious ... When I find Algiers transferred to Calais, I will tell you what I think ...”. That is, while the British had a direct national interest in stopping revolutionary excesses in France, they had no such interest in stopping slave-raiding by Algiers. Since no single nation can save the whole world, the object of rescue has to be selected. And national interest should help make that selection. What ‘progressive’ idealists dismiss as hypocritical inconsistency is in fact a properly cautious—conservative—exercise of political prudence. And prudence is a virtue.

Scotland and England

It wasn’t all about the economy, Stupid.

THE YEAR after my book on war had been published, my attention moved from the moral legitimacy of national interest to that of the nation itself. In September 2014, the referendum on Scottish independence was held. As an Anglo-Scot, born of a Scots father and an English mother and educated on both sides of the border, I had a dog in the fight: I was a visceral unionist. Nonetheless, I felt obliged to consider the arguments in favour of Scotland’s independence, in case the Scottish separatists might be right. After all, as a Christian I couldn’t confuse the United Kingdom with God. Nations aren’t divine; they come and go. The UK didn’t exist before 1707, the United States almost fell apart in the 1860s, and Czechoslovakia did fall apart in 1993. Maybe the separatists were right, and the UK had come to the end of its natural shelf-life. So, I listened. But after listening and reflecting, I concluded that Scottish independence was a dogmatic solution in search of a justifying problem.

On the other hand, I was dismayed by the strangled inarticulacy of advocates for the Anglo-Scottish Union as they tried to explain what the United Kingdom is good for and why its disintegration would be bad for everyone, including the Scots. The Conservative government seemed able to argue only in the base terms of pounds and pence, trying to woo voters to stay with the UK for the sake of few hundred quid. Yet, a full 45 per cent of Scots voters defied them, enchanted by a vision of a Better Scotland. It wasn’t all about the economy, Stupid.

To be fair, unionist inarticulacy was a symptom of the difficulty of describing the ground upon which we’d long been standing. One of the referendum’s benefits was that it forced unionists like me to lift up our feet, look down, and contemplate what it is that supports us. What I discovered is that the UK is good for three things beyond the economic advantages of a single market: an historic depth of multinational solidarity of which the European Union can still only dream, greater external security for liberal democracy, and the upholding of a humane international order.

Liberty and Empire

That’s what pushed me off the fence: the repressive aggression of the illiberal, ‘progressive’ left.

THE SCOTTISH referendum campaign revealed something else, too: the political potency of colonial history. One argument in favour of independence that I came across is reducible to this equation: Britain equals empire equals evil. Independence, therefore, would be an act of national self-purification, in which Scotland would cleanse itself of complicity in Britain’s imperial past, with its worldwide abuse of hard power, and sail off into a bright, new, shiny, pacifist, sin-free, European future. However, having read about British imperial history for twenty years, I knew that the simplistic equation, ‘empire equals evil’, is historically untenable. Yes, the British Empire presided over a century-and-a-half of slave-trading and slavery, but then it became one of the first states in the history of the world to abolish both, before devoting the second half of its life to suppressing them all over the world from Brazil to New Zealand. So, here, empire equalled both slavery and anti-slavery, both oppression and emancipation.

What the Scottish separatist story made clear was the attractive power—greater than the lure of pounds and pence—of a morally uplifting national narrative, with which individuals can identify. So I began to think that someone needed to expose the separatists’ cartoonish denigration of the British imperial record and tell a truer and, frankly, nobler story about it That’s why, in July 2017, I collaborated with John Darwin, the eminent historian of global empire, to launch an Oxford research project called “Ethics and Empire”. While its aim wasn’t directly to defend the British imperial record, it did assume that empire could sometimes be a legitimate form of government.

After May 2020, when the Black Lives Matter movement came over the Atlantic in the wake of George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, the political potency of colonial history became even clearer. Here, the BLM narrative is that Britain today is systemically racist; that our systemic racism stems from our colonial past, which can be summed up in the word ‘slavery’; and that, therefore, we have to repudiate that past—to ‘decolonise’—in order to exorcise our persistent, white supremacist racism. This narrative has not only inspired the toppling of statues and erasing of names; it’s also fuelling support for the payment to Caribbean states of about £18 trillion’s worth of British reparations for slavery. So, in February 2023 I published an alternative, even-handed history in the form of Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning.

It was my nuanced view of the British colonial record that caused me to be dragged into the Culture Wars. In late November 2017 I published an article in the Times, which argued for what I thought was the incontestable view that we British can find in our colonial past cause for both shame and pride. Then in early December, I published an online description of the “Ethics and Empire” project. That was enough to provoke Dr Priyamvada Gopal of Cambridge University to tweet to her allies in Oxford, “OMG. This is serious sh*t. We need to SHUT THIS DOWN”. Shortly afterwards, in the space of a week, three mass denunciations were published online, the last signed by almost two hundred academics worldwide, demanding that Oxford University take the “Ethics and Empire” project out of my hands. Consequently, John Darwin abruptly jumped ship, Oxford historians declared an official boycott, the project was temporarily stalled, friends and colleagues stepped nervously away from me, and sympathisers insisted on meeting where no one could see us together.

That’s what pushed me off the fence: the repressive aggression of the illiberal, ‘progressive’ left. And that’s what made me aware that free speech and academic freedom are under threat in our universities. Believing that all human views are fallible and need testing, so as to expose errors and falsehoods and come nearer the truth, I took up the fight to conserve the cultural climate of free inquiry that I had hitherto taken entirely for-granted.

Law and Judgment

YET WHILE I do believe in the importance of legal rights in shoring up liberties such as the freedom to speak one’s mind, I don’t buy into the absolutism of rights-advocates. Apart from a very few legal rights that ought to obtain always and everywhere—say, against torture—whether a right should exist depends on the circumstances.

Take, for example, the current controversy over Israel’s conduct in Gaza. Some international lawyers hold the Israeli government guilty of a war crime for depriving the civilian population of their absolute, inalienable right to water. But that makes no sense. Suppose a situation where there is no water or no one is capable of supplying it. Or suppose a situation where a state has an overriding obligation to defend its own people against an aggressor, but it can’t do so effectively while supplying water to the aggressor’s civilians. In those circumstances, how can those tragically deprived of water be supposed to have a right to what cannot or what may not be delivered? A basic human need only amounts to a right where supply exists and delivery is possible and obligatory. The right comes and goes, according to circumstances. So, whether or not civilians in Gaza have a right to water depends on Israeli intentions, their attempts to minimize civilian risks, and the importance of their military objectives.

Because I think that most rights are contingent upon circumstances, I’m deeply sceptical of lists or charters of abstract rights. Here, again, I find myself aligned with Burke in his fierce denunciation of revolutionary France’s Declaration of the Rights of Man. The problem with abstract rights is that they hand an unelected judicial oligarchy the power to override an elected legislature on highly controversial public issues, thereby compromising the democratic legitimacy of the law. Thus, in 2015 the Supreme Court of Canada found the Canadian parliament in violation of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms in failing to permit assisted suicide—despite the fact that the Canadian parliament had repeatedly considered the matter and recently decided against granting a right.

That’s why I’ve come to the view that the UK should withdraw from the European Convention of Human Rights and the jurisdiction of the Strasbourg court. While its defenders protest that the convention was largely a British creation, the truth is that the British government subscribed to avoid political embarrassment—and against the strong advice of the chief justice, who warned that subscription would hand a host of political hostages to judicial fortune. If the US, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand can manage without the supervision of an international court, I am confident Britain can, too.

IN SUM I believe that human dignity derives from serving objectively valuable ‘goods’; in Britain’s traditional, mixed constitution, which recognises the importance of goods and duties that are given, not chosen; in the United Kingdom, because it continues to serve the good of its constituent peoples; in admiration for the humanitarian and liberal achievements of our imperial ancestors; in the unembarrassed pursuit of legitimate national interest; in the necessary use of hard power to fend off grave evils, near and far; in a liberal culture of free speech that aims at closer approximation to the truth; in well defined, legislated rights; and so in national independence of the European Court of Human Rights.

How is this creed ‘conservative’? Because it seeks to conserve Britain’s Christian tradition, its mixed constitution, the integrity of the United Kingdom, an even-handed appreciation of the worldwide achievements of our forebears, and the liberal culture of free thinking and speaking that took centuries to cultivate. Because, against ‘progressive’ idealism, it affirms the possibility of morally justified nations, national interests, national judicial independence, and military force. Because, against abstract rights that authorise rule by a judicial oligarchy’s fiat, it asserts rights prudently defined in view of particular circumstances by democratic legislators. And because it invokes the authority of Edmund Burke, twice.

So, Sir Roger, I have come off the fence: I confess that I’m a conservative. But, no, Bishop Richard, that doesn’t make me a shallow pragmatist, obsessed with low taxes and a small state.

How refreshing you are to read! I have a similar story to share, although I won't be as eloquent as you—but perhaps there is charm in that difference, because it is emblematic of counterpoints of our cultures I still find appealing. (I am a muddy-boots American who had childhood dreams of becoming a pamphleteer and polemicist as much as I did of playing synth on Mtv.)

I, too, have recently come off the fence. No one encouraged me, though for some years there has been a small voice in my mind and heart that whispered with increasing urgency. During Covid and the BLM riots, it started shouting. I spent that time in the San Francisco Bay Area—the heart of American "liberalism", where I had lived for the previous fifteen years, enjoying the luxury of being politically complacent. I worked sixty-hour weeks, I played in two bands, I took for granted the freedoms I had, and I thought only marginally about the great, inspiring concepts with which I was raised.

My father's career as a high-ranking Army officer gave us a peripatetic lifestyle and placed us in locations as far-flung as Riyadh, Hiroshima, Washington, D.C., Oklahoma City, Honolulu, and the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. Being exposed to such disparate cultures from my earliest years instilled in me a longing to know more about my own. I studied American history with zeal in my adolescence, reading Paine, Adams, de Tocqueville; all the greats. As a teen in Northern Virginia during the Reagan Eighties, it was cool to be able to discuss and debate with other daughters and sons of international diplomats. I *loved* it. I felt no compunction about supporting the president and relating his philosophies and wins back to the ideas in those books, particularly after the fall of The Wall.

Fast forward to 2020.

In Marin County, we locked down early and long—from March of '20 to June of '21. At first, my introvert nature viewed it as a godsend. Truly, the lockdown itself gave me the greatest gift I could ask for in the form of a remote-work career. As the events of 2020 continued to unfold, however, I started to perceive, for the first time in my life, the tightening grip of State Control, and the cult mentalities that support it, both of which Eric Hoffer warned about in The True Believer.

At night, my husband and I compared notes about the implications of the latest vaccine mandate, the latest statue to be toppled, and the latest friend to be unwilling to entertain a critical discourse about any of it. As the months dragged on and events became more extreme, we wondered aloud how close the riots and unchecked crime would get to us and whether we should arm ourselves, whether we would be fined, fired, or jailed for having forged vaccine cards, and whether or not we would ever be able to share our thoughts about it all with anyone but each other.

I've always been a Creative, and I found my creative urges begin to shut down. I second-guessed everything I said for fear of cancellation. That was tantamount to emotional expiration.

The anxiety of those years threw me into a chronic, low-grade, depression as it did for many. I had time and space to consider what the inevitable march of State Control looked and felt like, and it terrified me. I went back to my history books and read about Stalin's Soviet Union, about the rise of the Third Reich, about North Korea and Communist China. For years, I'd rested assured that the specter of totalitarianism had been vanquished so far from typical American life as to pose no threat at all—a relic of the Cold War. In 2020, I started to realize that wasn't true. In the years I'd been away from the nation's political debate, leaving it to others to be involved, a bizarre attraction to Marxism had taken hold in many areas of society—particularly in California. I started to wonder if my parents had been right all along in their oft-expressed Conservative views.

As I observed and learned more, I tested my own deeply-held beliefs. I had long considered myself a Classically Liberal libertarian—somewhere in the middle—and like you, not wanting to box myself in. I examined the radical left that was making so much headway week-to-week and found it to be a frothing, vacuous, hypocritical zombie comprising nothing more than people who seemed brainwashed by outrage culture, competing for victimhood, and only interested in destruction, fear mongering, guilt-assigning, and justification for bad behavior. I also noticed that many of the worst offenders were "liberal" kids from wealth who, like their flower children forebears, trafficked in luxury beliefs and demonstrated a decided detachment from the need to offer solutions to any of the problems about which they so stridently shouted.

Things in the Bay Area became foreboding and uncomfortable enough that I began to think of life in terms of Prison Rules—at a certain point, you've got to pick a table. I went back to the well and reacquainted myself with the thinkers I loved in adolescence, and I found new ones to read and respect, like Brendan O'Neill, Thomas Sowell, Kathleen Stock, and Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who led me to you. I am forever grateful to all of you who have stuck out your necks to challenge the going narrative with cogent thought and well-reasoned arguments.

Over the course of the past five years, I've taken it all to the lab and emerged more committed than ever to what I feel are humanity's best hopes for a better future. Because of the liberal slurs and slanders on these systems, I find them still difficult to write without feeling like I'm committing a grievous social sin. After an extensive survey of belief systems, histories, political and economic systems, and a lot of self-reflection, I believe humanity's best hopes are found in Christianity and Capitalism. I believe, when used wisely and in concert, they offer more people a better shot at a higher quality of life than most of our species has ever known. Those two "C"s brought me to the third one—Conservatism.

Having been closer than comfortable to the upending and potential loss of my own freedom of expression, freedom of movement, freedom of religion (to be a professed Christian in SF is to be a social leper), I chose my table. Being a creative and an artist, I am supposed to be none of these things, but I've always viewed myself as an Apollonian artist, not a Dionysian one. To be able to admit that is sweet relief.

Yes, I support pragmatic economics, border sovereignty, and good stewardship of a smaller government, but beyond that, I believe in learning from the past, conserving the good, leaving the bad, and building on what we've done that was worthwhile. Plenty of it has been worthwhile!

Like you, I never bought into the "frivolous trashing of the past" and continue to believe that we will repeat history if we are afraid to learn it and look it in the eye, challenge it, and conserve the wisdom it can offer.

Another hallmark of Conservatism (at least in this country) is a penchant for efficiency. What is less efficient than repeating the same mistakes generation after generation and learning nothing?