Culture War in Britain: Part 3

Colonialism and Elections

This post concludes a three-part series on the culture wars in Britain. In the first part I discuss its origins and its chilling effect on free speech. The second part touched on the uncontroversial subjects of gender and race. This final addition is similarly spiced.

‘Decolonisation’ versus the security of the West

The colonial front of the Culture Wars is related to the racial one. One reason that British colonial history has become controversial is that it is used by the British representatives of Black Lives Matter to argue that the systemic racism of Britain today is rooted in our colonial past, which can be equated with slavery. Therefore, we must repudiate our colonial past, pulling down the statues of imperial heroes, in order to exorcise our lingering racism.

In addition to a more truthful account of race relations in Britain today, what’s also at stake on the colonial front is the integrity of the United Kingdom. This is because some Scottish separatists make an argument that can be distilled into this equation: Britain equals Empire equals Evil. Accordingly, Scottish independence would be an act of national self-purification in which, by cutting the cords binding it to a Britain discredited by the imperial abuse of hard power, Scotland is free to sail off into a bright, new, shiny, sin-free, European future.

Bound up with this is the third thing at stake on the colonial front of the Culture Wars: the strength and self-confidence of the West. Britain remains an important, if secondary, pillar of liberal democracy in the world. And not many things would delight the West’s totalitarian enemies in Moscow and Beijing more that to witness the disintegration of the United Kingdom. Recalling the final days of the Scottish referendum campaign in September 2014, the then British ambassador to the UN, Mark Lyall Grant, has written: “my Russian opposite number sympathised with barely suppressed glee at the prospect of the UK dismembered and its permanent seat on the security council called into question. It was clear to me that Scottish independence would have had a devastating impact on the UK’s standing in the world, much greater than withdrawal from the EU ever would”.

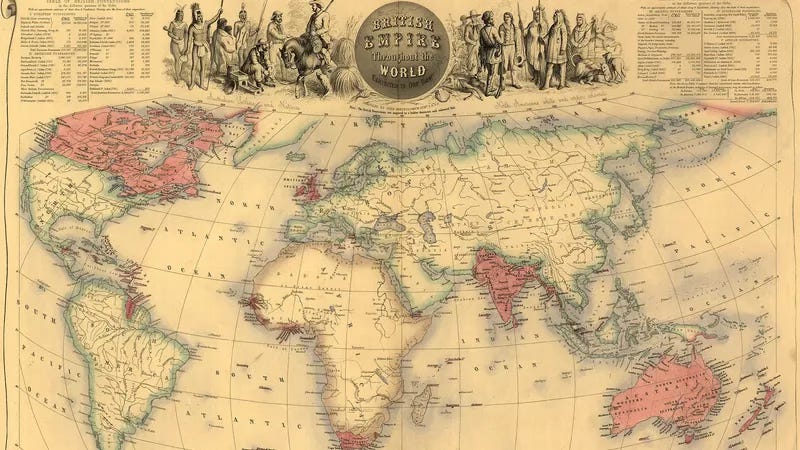

What is more, the obsession of the ‘decolonisers’ with the British Empire—rather than, say, the Arab or Chinese or Russian or Comanche or Zulu one—is curious and begs explanation. One is that their real target is the record of the West, for which the British Empire is a proxy. Certainly, the story they tell about the British Empire as a litany of racism, economic exploitation, cultural repression, and unconstrained violence is eagerly picked up and broadcast all over the world by the likes of Al Jazeera. It also fuels the demand by Caribbean states for reparations for slavery from Europe, quantified in June of this year by the Brattle Group as amounting to $108 trillion.

However, as I have demonstrated in my recent book, Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, the ‘decolonising’ narrative is wildly distorted, not least in its dogged refusal to recognise that the British Empire was one of the first states in the history of the world to abolish slave-trading and slavery and that it then used its imperial power to suppress them both from Brazil, across Africa, to India and Australasia. And yet, my attempt to correct the record has been met with the thought-resistant fist of repression, not only among university students and professors, but also among the junior staff of my original publisher at Bloomsbury.

So, what’s at stake in the Culture War over colonial history? First, the exposure of a false narrative about race relations in Britain today. Second, the exposure of a false narrative that inflates the case for Scottish independence and the disintegration of the UK. And third, the exposure of a false narrative that undermines confidence in the liberal West, at home and abroad, at a time, when illiberal powers in Moscow and Beijing are rattling their sabres in Ukraine and at Taiwan.

The Culture Wars and electoral advantage

So, what’s at stake in the Culture Wars? The well-being of vulnerable young people disturbed by questions of gender and sex; the accurate diagnosis of the causes of disadvantage suffered by some ethnic groups, so as to enable effective redress; security against groundlessly divisive racial politics; the integrity of the United Kingdom; faith in the West and security against opportunistic demands for reparations for slavery; and the freedom from illiberal, authoritarian repression to question and contradict false assumptions and narratives that threaten all of these.

But there is one thing more.

No doubt the cost of living, the funding of healthcare, and the rate of immigration are foremost in citizens’ minds. Nevertheless, Culture War concerns will often be there, too. We have recently spotted two straws blowing in the political wind. One was the widespread opposition that the then First Minister of Scotland, Nicola Sturgeon, aroused by stubbornly proposing a law that would effectively permit transgender self-identification. For the first time, Teflon Nicola found herself fatally exposed as she marched out ahead, only to find that lots of her wonted supporters were standing still, their arms sullenly folded. It was the gender issue that had broken their trust in her, leading her to resign in March 2023.

The second straw was the defeat later that year of the “Voice to Parliament” campaign in Australia. That campaign would have given Aboriginal people—one of many ethnic groups in Australia and comprising only 3.5 per cent of the total population—uniquely privileged representation. Propelled by a sense of colonial guilt—to quote Fraser Nelson in the Telegraph—“the Yes campaign outspent No by five to one. It had sports stars, companies and the whole establishment on its side, yet still lost in every Australian state”. The opposition was led by the Aboriginal politician, Jacinta Nampijinpa Price, who argued that colonialism has benefited Aboriginals, that the ‘re-racialisation’ of Australia into Manichaean camps of ‘white’ and ‘black’ should be resisted, and that attention should focus instead on addressing unfair disparities, no matter what the skin-colour of their victims. Price’s message strongly echoes those of Rakib Ehsan’s book and the Sewell commission—and it won decisively by six votes to four.

These two straws in the political wind find broader social scientific backing in Eric Kaufmann’s Policy Exchange report, The Politics of the Culture Wars in Contemporary Britain. From a YouGov poll in May 2022, Kaufmann concluded that “the British public leans approximately two to one against the cultural leftist position across twenty culture wars issues”. These, therefore, form ideal ground “on which conservative parties can unite both the right and the centre-ground, while creating divisions between the centre-left and the far left”.

The election of President Trump appears to be fueling an anti-woke counter-revolution in the United States, which is perhaps echoed in the surge of support currently enjoyed by Reform in the UK.

So, all those phenomena reveal the final thing at stake in the Culture Wars: votes.